1. 引言

条件性恐惧是如何形成的呢?巴甫洛夫条件作用是研究条件性恐惧习得、存储、提取和消退等过程的理论模型(Kim & Jung, 2006; LeDoux, 2000; Maren, 2001; Rabinak, Orisini, Zimmerman & Maren, 2009, Pape & Pare, 2010; Schreures, Smithe-Bell & Burhans, 2011)。即在对个体进行不可逃避的厌恶刺激(无条件刺激,unconditioned stimulus,US,如电击)与中性刺激(条件刺激,conditioned stimulus,CS,如灯光、声音或训练环境)的联结匹配训练(CS-US),训练后当动物再次接触这个中性刺激CS时就会引发条件性恐惧反应。然而,如果条件刺激CS反复单独呈现而不匹配厌恶刺激时(CS-no US),那么个体先前习得的对CS的条件性恐惧反应会渐渐消退(Davis, Walker & Myers, 2003; Bouton, Garcia-Gutierrez, Zilski & Moody, 2006; Kindt & Soeter, 2013)。从这一理论模型来看,形成条件性恐惧的主要因素是与CS匹配联结的US的刺激性质。

然而,在一些情境中,发现除了刺激性质导致恐惧之外,刺激事件出现的概率,即预测水平也会引起条件性恐惧,表现出预测偏向。比如,暴露在不可预测情境下电击的老鼠表现出广泛性胃溃疡,而在可预测情境下接受同等数量和强度电击的老鼠的胃溃疡症状却明显减少(Seligman & Binik, 1968; Weiss, 1971)。在以健康群体为研究对象,发现相比可预测的厌恶刺激,个体对不可预测的厌恶刺激表现出更显著的生理反应(Grillon, Baas, Lissek, Smith & Milstein, 2004)。分别以创伤后应激障碍(post traumatic stress disorder, PTSD)患者、惊恐障碍(panic disorder, PD)患者作为研究对象,也得出了一致的结论:相对于可预测的厌恶刺激,PTSD、PD患者对不可预测的厌恶刺激表现出焦虑水平升高(Grillon, Lissek, Rabin, McDowell, Dvir & Pine, 2008; Grillon, Daniel, Lissek, Rabin, Bonne & Vythilingam, 2009)。但是,也有研究表明动物和人类对于非厌恶刺激(正性或中性刺激)也出现预测性偏向(Cantor & LoLordo, 1970)。这些实验结果表明预测水平在条件性恐惧形成过程中是一个重要刺激或影响因素。

事件相关技术对恐惧进行测量,其原理是基于既往文献对习得记忆和消退记忆关系的研究(Bouton, 2002; Rescorla, 2004),主要对P2,N2,P3和LPP四个成分进行分析。其中早期波幅P2和N2波幅和潜伏期主要反应消退和习得阶段早期对US的探测。P3和LPP的波幅,尤其是P3b-LP的波幅则主要对消退的程度进行量化测量。由于ERP技术在时间上的精确性,同时ERP波幅的测量是刺激锁定的,在刺激出现前后很短的时间,对其神经机制有精确的反应,其指标较皮温、皮电等生理指标更加精准。

综上所述,在条件性恐惧形成过程中,刺激性质与预测水平是两个重要的影响因素。在前人研究的基础上,有待进一步探索的是二者是存在交互作用,还是单独起作用。如果存在交互作用,在何中情况下进行;如果单独起作用,即分离作用,如何分离这两种因素以及分离时所依赖的神经基础。这些问题的解决有助于我们进一步理解条件性恐惧形成的内在机制,为基于条件性恐惧的情绪障碍,如创伤性应激障碍、广泛性焦虑障碍等临床治疗提供理论依据。为此,本研究采用事件相关电位,探索预测水平与刺激性质在影响条件性恐惧形成时的脑机制分离时程差异特点。

2. 方法

2.1. 被试

采用焦虑–特质量表(Spielberger, Gorsuch & Lusthene, 1970)测试14名在校大学生(状态焦虑:M = 37.43, SD = 8.30;特质焦虑:M = 42.93, SD = 9.03),男8人、女6人。年龄范围在18~23岁,平均年龄20.5岁,标准差2.45。被试均为右利手,无躯体疾病及精神障碍,视力或矫正视力正常。被试均采用自主报名的方式参与实验,实验前签署知情同意书,实验完成后给予一定的报酬。本实验得到学校伦理委员会的批准。

2.2. 实验设计

本实验为两因素被试内实验设计,自变量为刺激性质(中性刺激、负性刺激)和预测水平(可预测,不可预测)。因变量为行为指标(正确率和反应时)和生理指标(刺激性质和预测水平下诱发的ERP成分的平均波幅)。

2.3. 刺激材料

从国际情绪图片库中(Lang, Bradley & Cuthbert, 2008)的负性图片库中,随机选取30张作为负性刺激(平均唤醒度:M = 6.32,SD = 0.63;平均愉悦度:M = 1.88,SD = 0.34);从中性图片库随机选取30张作为中性刺激(平均唤醒度:M = 2.92,SD = 0.61;平均愉悦度:M = 4.98,SD = 0.32)。共60张图片作为US。对两类图片唤醒度和愉悦度分别进行独立样本t检验,差异显著(唤醒度:t(58) = 41.69,p < 0.001;愉悦度:t(58) = −24.58,p < 0.001)。实验图片分辨率均为100像素/英寸,大小统一为13 cm × 10 cm。另外五种几何图形(如:圆形,三角形)作为CS。

2.4. 实验流程

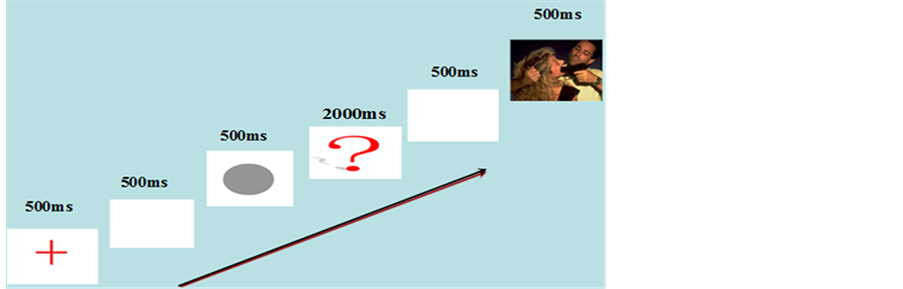

实验开始,首先对被试的焦虑状态进行评估,每个被试都要完成状态-特质焦虑量表。被试戴好电极帽后坐在一间光线柔和的隔音室里,被试双眼与屏幕距离100 cm,水平与垂直视角分别为7.44˚ × 5.72˚。首先在白色屏幕中心会出现一个500 ms的红色“+”注视点,提示实验即将开始,接着是400 ms的空屏,然后屏幕会呈现一张白底灰色的几何图形图片,呈现时间是500 ms,随后是500 ms的白屏,接着出现一个2000 ms的问号“?”,要求被试预测几何图形后出现的图片是负性还是中性,如果是负性刺激,用左手按“F”键;如果中性刺激,用右手按“J”键,接下来出现500 ms的负性或中性图片。具体流程请见图1。

所有刺激在2个block中随机呈现,一个是可预测block,另一个是不可预测block,2个block顺序随机呈现。在可预测block中,正方形后一直呈现负性刺激,而圆形后一直呈现中性刺激,正方形和圆形,中性刺激和负性刺激出现的概率都是一致的。在不可预测block中,为了避免与可预测情境产生干扰,我们采用棱形和椭圆,两种图形后面都有可能出现中性刺激或负性刺激,其概率控制在33%。

2.5. ERP记录

实验仪器为Neuroscan(德国)脑电记录系统,参考电极置于右侧乳突,前额接地,采用64导电极帽记录脑电,同时记录水平眼电和垂直眼电。滤波带通为0.01~100 Hz,采样频率为500 Hz/导,头皮电阻降至5 kΩ以下。进行离线分析(off-line analysis),离线分析时通过对左侧乳突再参考,实现以右侧乳突和左侧乳突的平均值为新参考,分析时程(epoch)为1000 ms,其中刺激呈现前200 ms作为基线。实验中每个被试共获得4种脑电(可预测/中性、可预测/负性、不可预测/中性、不可预测/负性)。

2.6. 数据分析

根据总平均图和参考文献确定ERP各成分的时间窗口,参考以往研究(Stadler, 2006),本研究的统计分析选择3个电极位置(Fz、Cz、Pz),分别对四种情况进行分析:可预测情况,时间窗为N2(120~180) ms,P3(250~350) ms;不可预测情况,时间窗为N3(220~320) ms;中性刺激在可预测与不可预测情况,时间窗为LPP(300~450) ms;负性刺激在可预测与不可预测情况,时间窗为N1(50~150) ms,LPP(350~450) ms。

对四种情况采用被试内重复测量方差分析,并进行简单效应分析。采用SPSS17.0统计软件进行数据处理,并对不满足球形检验的统计效应采用Greenhouse-Geisser法矫正p值。

3. 结果

3.1. 行为结果

在可预测情况下,每个被试对负性图片和中性图片按键反应都达到了94%以上的正确率;在不可预测情况下,被试对负性图片和中性图片按键反应的平均正确率是34.5%。对被试在两种不同预测水平(可预测/不可预测)的反应时进行t检验,结果显示被试在不可预测条件下(M = 285.15, SD = 18.64)比在可预测条件下(M = 320.75, SD = 18.46)反应要慢。这说明,不论图片是负性还是中性,图片出现的预测性影响了被试的行为反应。

Figure 1. Experimental procedures

图1. 实验流程

3.2. ERP结果

3.2.1. 可预测情境下中性与负性刺激的脑电结果

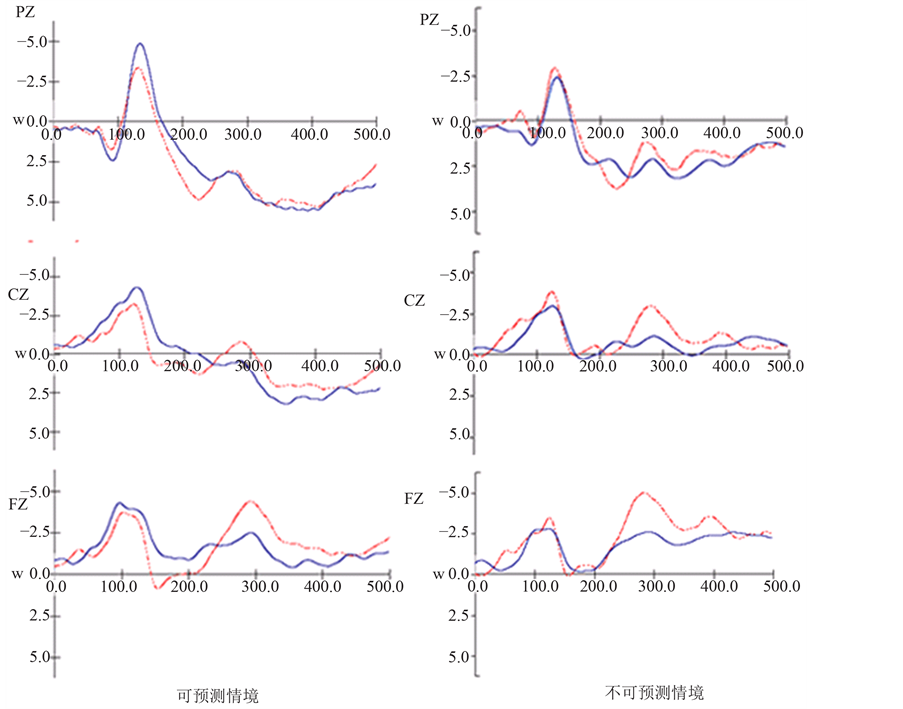

在可预测情境下,对120~180 ms时间窗口内两种刺激性质对CS所诱发的平均波幅进行刺激性质 ×电极点重复测量方差分析。结果显示,电极点的主效应不显著(F(2, 41)= 2.37, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.18),刺激性质主效应显著(F(1, 13) = 3.59, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.14)。电极点与刺激性质的交互作用不显著(F(2, 41) = 2.97, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.14)。对300~500 ms进行刺激性质 × 电极点重复测量方差分析。电极点的主效应显著(F(2, 41) = 3.96, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.19),刺激性质主效应显著(F(1, 13) = 4.01, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.24)。电极点与刺激性质的交互作用显著(F(2, 41) = 3.48, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.17)。从PZ到FZ点,波形从正波向负波偏移,两种刺激性质在CZ和FZ点所诱发的波幅差异最大,在PZ点差异不显著(p > 0.05)。结果表明,两种刺激性质在可预测情境下,在加工早期就产生了分离。在晚期加工区域主要集中在脑前顶区和枕区。并且从波形可以发现在250 ms左右两种中性刺激发生了返转,即负性刺激比中性刺激所诱发的波形更正,如图2所示。

3.2.2. 不可预测情境下中性与负性刺激的脑电结果

在不可预测情境下,对220~320 ms时间窗口内两种刺激性质对CS所诱发的平均波幅进行刺激性质× 电极点重复测量方差分析。结果显示,电极点的主效应显著(F(2, 41) = 1.92, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.09),刺激性

Figure 2. ERP of the prediction and unprediction condition on the neutral and negative stimulus

注:蓝色代表负性刺激,红色虚线代表中性刺激。

图2. 可预测情境和不可预测情境下,中性刺激与负性刺激的ERP

质主效应显著(F(1, 13) = 6.01, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.26)。电极点与刺激性质的交互作用显著(F(2, 41) = 6.54, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.14)。从脑电波形图可以看出,在0~250 ms,两种刺激在不同电极点之间所诱发的波形没有差异(p > 0.05)。数据表明在早期加工过程中,在不可预测性况下,条件性恐惧不受刺激性质的影响,而是受不可预测水平的影响,而在后期的加工过程中,才受到刺激性质的影响,从而表现出对两种不同刺激性质的波形差异,如图2所示。

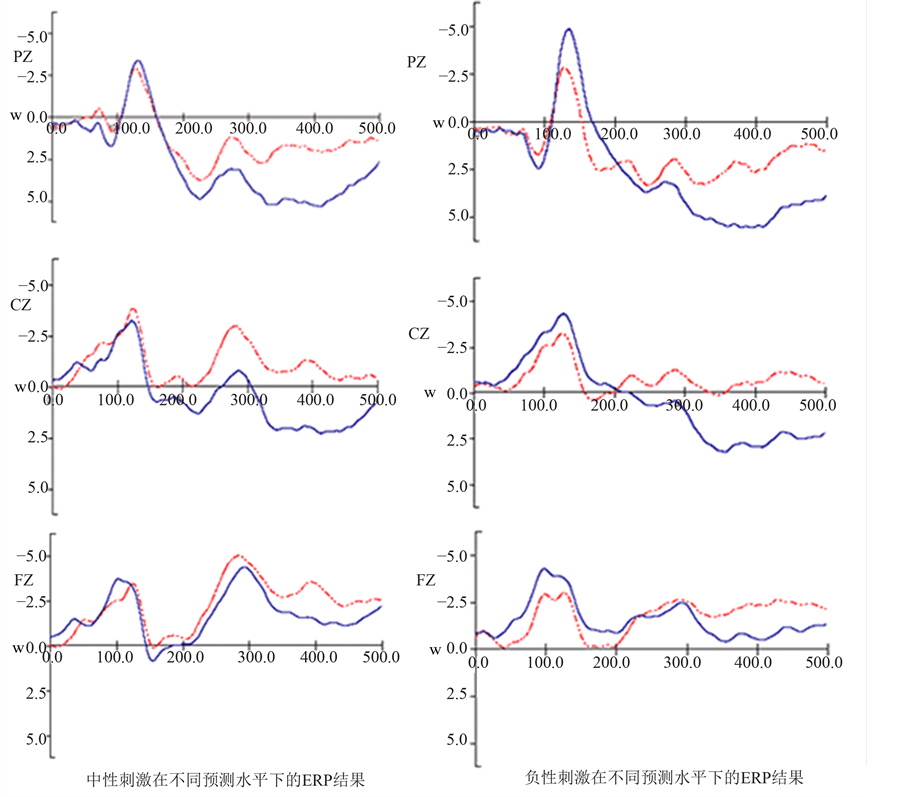

3.2.3. 中性刺激在不同预测水平上的脑电结果

对中性刺激,在300~450 ms时间窗口内在不同预测水平上对CS所诱发的平均波幅进行预测水平 ×电极点重复测量方差分析。结果显示,电极点的主效应显著(F(2, 41) = 6.01, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.21),预测水平主效应显著(F(1, 13) = 6.26, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.24)。电极点与预测水平的交互作用显著(F(2, 41) = 5.86, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.14)。从波形上看在不同预测水平上,在加工早期两种预测水平不存在显著性差异。但是在后期存在显著性差异,产生分离。数据表明中性刺激本身并不构成条件性恐惧,但是不可预测水平情境中,会影响晚期加工方式,这种差异在前额和顶区表明明显,如图3所示。

Figure 3. ERP of the neutral and negative stimulus under the prediction and unprediction condition

注:蓝色代表不可预测,红色虚线代表可预测。

图3. 中性刺激和负性刺激在可预测与不可预测情境下的ERP

3.2.4. 负性刺激在不同预测水平上的脑电结果

对负性刺激,在不同预测水平上对CS所诱发的平均波幅进行预测水平 × 电极点重复测量方差分析。在120~180 ms时间窗口内,电极点的主效应不显著(F(2, 41)= 6.76, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.05),不同预测水平之间的差异从PZ至FZ点,差异逐渐增加大,且差异显著(F(1, 13) = 5.21, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.24)。电极点与刺激性质的交互作用不显著(F(2, 41) = 7.56, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.14)。在350~450 ms时间窗,电极点的主效应显著(F(2, 41) = 1.46, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.13),预测水平主效应显著(F(1, 13) = 6.48, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.24)。电极点与刺激性质的交互作用显著(F(2, 41) = 4.98, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.18)。从PZ到FZ点,波形从正波向负波偏移,不同预测水平在PZ和CZ点所诱发的波幅差异最大,在FZ点差异最小。这些结果表明不同预测水平的差异在晚期加工区域主要集中在脑前额区和顶区。并且可以发现在早期加工时,不同预测水平存在差异,出现了分离,即在不可预测与负性刺激存在交互作用,会影响后续对恐惧情境的知觉和感受,如图3所示。

4. 讨论

条件性恐惧的习得不仅受影响刺激性质的影响,而且受预测水平的影响,即预测偏向。在之前的一些研究中也发现了预测偏向的影响(Moberg & Curtin, 2009; Sun et al., 2011; Jin et al., 2013)。在可预测情况下,恐惧的习得主要受刺激性质的影响。而在不可预测情况,刺激性质的影响减弱,负性与中性刺激在加工早期ERP波形差异不显著,恐惧的习得更受预测水平的影响。对于中性刺激,在不同预测水平上在加工晚期差异显著,且负性刺激在不同预测水平在顶区以及枕区加工早期就开始分离,且在后期由顶区到枕区差异减少,表明负性刺激与预测水平存在交互作用。从这些结果看来预测水平与刺激性质存在分离与交互作用。

在巴甫洛夫条件作用,条件性恐惧的习得是CS作为信号提示其后存在US,即可预测,但是在生活中,另一种重要刺激是不可预测刺激(无线索作为信号提示)。临床焦虑个体普遍存在预测性偏向。相对于不可预测刺激,对于可预测刺激的预测性偏向被认定为焦虑和焦虑障碍的核心特质(Foa, Zinbarg & Rothbaum, 1992)。研究发现,无论是动物,还是人类都对厌恶刺激具有预测性偏向,或者说,相对于不可预测的厌恶刺激,动物和人类更喜欢可预测的厌恶刺激,因为可预测的厌恶刺激在心理、生理和行为方面对个体的伤害更轻,影响更小(Badia, Suter & Lewis, 1967; Lockard, 1965; Pervin, 1963)。个体的预测性偏向产生的原因是什么?安全信号假设理论(safety-signal hypothesis) (Seligman & Binik, 1977)认为,当个体处于在可预测情境中,即能通过线索来预测威胁刺激时,只要线索不存在,那么就意味着威胁刺激不出现,则表明当前是安全的状态。然而,当个体处于不可预测情境下,没有线索作为信号提示,即使处于安全时期也没有信号提示,那么个体就会处于持久的焦虑或者焦虑预期中。因此,在不可预测情境下,个体的焦虑水平要比不可预测情境下低,生理反应也更加强烈。

Felmingham等人(2009)在研究中引入中性刺激,结果表明,与对照组相比,PTSD患者对于不可预测的中性刺激存在差异,而对可预测性的中性刺激则差异不显著。研究者认为不可预测中性刺激对焦虑障碍的患者可能存在潜在威胁,刺激的作用可能等同于威胁刺激。这一结果加强了对不可预测刺激的偏向是焦虑障碍核心机制的理论,将预测偏向扩大到中性刺激。而中性刺激在不可预测情境中也能引起恐惧反应,从本实验中我们可以看出,中性刺激在不同预测水平上,在早期加工过程中没有差异,而在晚期成分加工过程中差异显著。可以得出在中性刺激中影响恐惧习得的并不在于刺激,而在于不可预测。从决策研究角度来说,不确定本身就是一种风险,风险可以构成厌恶刺激,从而引起个体在决策过程中处于焦虑和不安(庄锦英,2006)。这一点也可以在负性刺激在不同预测水平情境中的波形差异中也可得到证实。

综上所述,对于条件性恐惧的形成受预测水平和刺激性质的影响,对中性刺激情境下,影响恐惧形成的主要是预测水平,刺激性质与预测水平存在分离;而相对于负性刺激,恐惧的形成不仅受刺激性质的影响,而且也受预测水平的影响,二者在此情况下存在交互作用。

基金项目

广东省大学生创新创业项目(1057413146)资助。

NOTES

*通讯作者。