1. 引言

传统合金的研究与发展一直局限于以一种或二种金属元素为主的思路内,多主元高熵合金就是20世纪90年代左右由叶均蔚提出的一种全新的合金设计理念 [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]。就目前已有研究成果来说,高熵合金可以定义为由5到13种金属元素按照等原子比或近似等原子比(各组元金属原子的百分含量一般不超过35%)合金化后,混合熵高于合金整体的熔化熵而形成高熵固溶体结构的合金 [6] [7] [8]。高熵合金跟传统合金相比是由多种金属元素组成,因此体现出了由多种元素混合而产生集体效应而呈现出高熵特色,多种金属原子间虽然排列混乱,但是呈现出的却是非常简单的结晶相 [3] - [8]。这种高熵特色不但会使合金微结构简化,而且可以使结构更倾向于纳米化或者是非晶化 [2] [3] [4] [5] [6]。除了高熵效应,研究成果还总结了高熵合金具有动力学上的迟滞扩散效应、结构上的晶格畸变效应及“鸡尾酒”效应 [6] [7] [8]。正因为这四大效应的共同影响,高熵合金才表现出许多优良特性,如高耐腐蚀性、高强度、高硬度、高耐热性 [5] [6] [7] [8] 等,因此相较于传统合金且有较大的优越性及研究发展空间。目前对高熵合金的研究大都集中在制备方法、微观结构或宏观力学性能上,2004年叶均蔚团队采用真空熔炼法首次制得了AlCoCrCuFeNi合金 [8],然后对其各种性能进行研究 [9] [10] [11] [12]。2008年印度科学家通过另一种方法,即机械合金化制得了AlFeTiCrZnCu合金 [13],并通过实验研究了其力学性能和热固结性能 [14]。印度科学家的研究结果表明,AlFeTiCrZnCu高熵合金系是简单结构的体心立方晶体,所含有的六种金属元素之间也没有形成结构复杂的金属间化合物,致密性很好,而且还且有较高的硬度。2014年科学家偶然之间发现了一种由FeMnCoCr组成的高熵合金 [15],这种合金在冷轧退火之后同时具有了较高的强度及较好的延展性。这一发现完全颠覆了材料科学领域中的一个经典常识,强度越高延展性就越差。科学家们认为高熵合金这种独特的行为机制可能源于这种材料具有多种原子重排方式,因而具有多种防止裂纹扩散的机制,从而让合金能够吸收所受的冲击。在相变之前,合金内部实际包含了两种具有不同晶体结构的高熵合金。而在变形之后,高熵合金的晶体结构发生了变化,并表现出不同寻常的高延展性与高强度的组合。

目前已有研究大都是通过实验来研究高熵合金,工作量较大,而且实验过程中还可能存在一些不确定性。为了更好地研究高熵合金的元素影响机制,希望通过理论计算得到的结果来解释高熵合金的某些特性。基于密度泛函理论的第一性原理从头计算是量子力学中一种研究多电子体系的方法,该方法一般情况不需要任何参数,只用一些基本的物理量就能得到体系的基本性质,通过理论计算结果可以从微观层面来讨论合金的宏观特性,在研究分子或是凝聚态的性质中有广泛应用。已有研究如第一性原理计算Ca-X系 [16]、Al-Ni系 [17]、Al-Ru系 [18] 金属间化合物、CaTiO3的缺陷及掺杂 [19] [20]、Mn掺杂GaN(11-00)的磁性能 [21] 及原子电子结构 [22] 等。Cu元素本身是面心立方晶体结构,密度是8.96 g/cm3,是高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu六种元素中密度最大的。本文建立高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu第一性原理计算的晶体结构模型,计算高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu在不同Cu元素含量时的晶体结构及性能,希望能进一步了解Cu元素含量对其的影响。

2. 计算方法

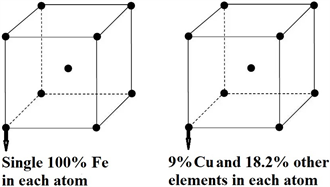

本文的第一性原理密度泛函理论计算是采用美国Accelrys公司出品Materials Studio软件中的CASTEP (Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package)模块 [23],它是基于平面波赝势的扩展,高熵合金的长程固溶体结构模型采用虚拟晶体近似(Virtual Crystal Approximation, VCA) [24] [25] [26] 的方法建立。印度科学家的研究表明高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu是简单的体心立方(Body-centered Cubic, BCC)晶体结构 [13],是不完全有序的,在建模过程中可能会产生所谓“虚拟原子” [25] [27],而长程的超胞结构模型在计算过程中也会积累误差 [26],为了减少这些情况,本文在单个BCC晶胞中的每个原子上用VCA的方法,如图1所示,这种方法能尽量避免建立超胞的长程结构所带来的计算过程复杂、计算时间过长及误差累积的缺点。

Table 1. Mole fraction and mass fraction of Cu, and mass faction of other elements

表1. Cu元素的摩尔含量、百分含量、相应其余元素的百分含量

表1中列出了高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu在Cu元素的摩尔含量不同时相对应的百分含量以及其它金属元素相应的百分含量。图1是以BCC晶体结构的高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu中Cu元素摩尔分数为0.5时的AlFeTiCrZnCu0.5高熵合金为例,此时Cu元素的摩尔含量为0.5,百分含量为9%,其它金属元素的百分含量为18.2%,即BCC结构中每个原子都含有9%的Cu元素及均为18.2%的其它金属元素。

计算过程中选择广义梯度近似(General Gradient Approximation, GGA) [28] 下的质子平衡方程PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof)泛函 [29] 来设置电子与电子之间的交换-相关函数,电子-离子间相互作用选择第一性原理中的模守恒赝势(Norm-conserving Pseudopotential, NCP) [30] 来处理,展开的平面波函数截断动能选择为770 eV,倒空间中k点的网格间距为默认设置的0.4 Å−1,电子极小化为默认的Pulay混合,选择10 × 10 × 10的剖分网格。

选择以上计算参数验证晶体结构的计算准确性。采用以上参数计算BCC晶体结构的Fe元素晶格常数为2.84 Å,实验值为2.86 Å [31],误差为0.79%,说明上述计算参数选择较为合理。

Figure 1. The model of crystal structure of HEA AlFeTiCrZnCu0.5 was built by VCA

图1. VCA方法建立高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu0.5的晶体结构模型

3. 结果与讨论

3.1. 结构性质

采用以上参数设置,优化了高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在不同Cu元素含量时的晶体结构,优化后高熵合金的密度和晶格常数在表2中列出。图2表示了高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCu晶格常数、密度与Cu元素含量之间的关系。由表2,图2可以看出,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的密度随着Cu元素含量的增大而增大,而晶格常数随着Cu元素含量的增大而减小。这可能是因为Cu元素是高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux所有的组成金属元素中密度最大的,而且Cu元素本身是也立方晶体结构。在Cu元素摩尔含量为2时,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的晶格常数最小但是密度不是最大。

Table 2. Lattice parameters and mass densities of HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表2. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的晶格常数和密度(x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

3.2. 弹性性质

通过对优化后高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的晶体结构进行计算,得到高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在Cu元素含量不同时的弹性常数Cij、体积弹性模量K、杨氏模量E、泊松比v。Cu元素摩尔含量不同时AlFeTiCrZnCux合金的弹性常数Cij列于表3中,因为已有研究表明该合金的晶体结构是简单的立方晶系 [13],立方晶系弹性常数只有C11、C12及C44三个。弹性常数不但是表征材料弹性的物理量,还决定了其力学稳定性,力学稳定性是指在外力作用下,材料依然保持原有状态的能力,根据立方晶系金属材料力学稳定性判据 [32]:

Figure 2. Relationship to the lattice parameters and mass densities among the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux with different Cu content

图2. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的晶格常数及密度与Cu元素含量的关系

(1)

高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux只在不含有Cu元素时才符合立方晶系的力学稳定性判据,说明Cu元素含会影响高熵合金的力学稳定性。

Table 3. Elastic constants (Cij) of the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3) (GPa)

表3. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的弹性常数(Cij) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3) (GPa)

Table 4. Young’s modulus (E, GPa), bulk modulus (K, GPa), and Poisson’s ratios (v) of HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表4. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的杨氏模量E (GPa)、体积弹性模量K (GPa)、泊松比v (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

Figure 3. Relationships of Young’s modulus E and bulk modulus K to the mole fraction of Cu for the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux

图3. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的杨氏模量E、体积弹性模量K随Cu含量的变化

Table 5. Bulk modulus K of the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux by VRH approximation (GPa) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表5. 采用VRH近似计算的高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的体积弹性模量K (GPa) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

Table 6. Shear modulus G of the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux by VRH approximation (GPa) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表6. 采用VRH近似计算的高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的剪切模量G (GPa) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表4中是高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在Cu元素含量不同时的杨氏模量E、体积弹性模量K、泊松比ν的计算结果。杨氏模量E (Young’s modulus)是纵向的弹性模量,即金属材料在弹性限度内抵御抗压或抗拉的物理量,是外力作用下单向拉压的正应力与线应变的比值。它是衡量金属材料产生弹性变形的难易程度,当杨氏模量E越大,金属材料在纵向产生弹性变形所需的应力就越大,金属材料的刚度就越大,即在一定应力作用下,产生的弹性变形就越小。由表4中可以看出高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的杨氏模量E只在没有Cu元素时为正值,说明Cu元素含量的增加会降低其弹性变形。体积弹性模量K是弹性体受到静水压时与体积应变的比值,是反映金属材料抵抗断裂能力的弹性模量。表4及图3可以看出随着Cu元素含量增加高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的体积弹性模量K减小,因此Cu元素含量增加会降低高熵合金抵抗断裂的能力。

Table 7. Calculated Poisson’s ratios (v), ratios of shear modulus (G) to bulk modulus (K) for the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表7. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的泊松比v、剪切模量G与体积弹性模量K的比值(x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

为了进一步了解高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在Cu元素含量不同时的力学性能,采用Voigt-Reuss-Hill (VRH)近似 [33] 计算的体积弹性模量KV、KR、KH,剪切模量GV、GR、GH结果在表5,表6中。由表5中计算结果看出采用VRH近似计算的高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux不同Cu元素含量时体积弹性模量K并明显差别,但是表6中剪切模量G的计算结果相差很大,在Cu元素摩尔含量为0.5及1.5时剪切模量G的计算结果出现了负值。

此外泊松比v、剪切模量G与体积弹性模量K的比值是决定了金属材料的脆/韧性的物理量。研究表明泊松比为0.33左右时金属为韧性材料,其余是脆性材料 [34];以剪切模量G与体积弹性模量K的比值为判定依据时,以0.57为分界点,小于0.57时为韧性材料,大于0.57时为脆性材料 [35]。

高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在Cu元素含量不同时的泊松比v、剪切模量与体积弹性模量的比值在表7中。可以看出,判断金属材料的脆/韧性若以泊松比v作为判定依据时,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux无论含不含有Cu元素都为脆性材料,与Cu元素含量无关;以剪切模量与体积弹性模量的比值作为判定依据时,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux只有不含Cu元素时才可以看作是韧性材料,Cu元素含量增加改变了其脆/韧性。很显然金属材料的脆/韧性判定依据不同时,合金的脆/韧性就不同。这是因为泊松比v是金属材料单向受拉压时横向正应变与纵向正应变的比值,是金属材料弹性常数中反映横向变形的,但是剪切模量是材料弹性限度内切应力与切应变的比值,是纵向变形的弹性常数,是衡量金属材料抵抗切应变的能力。

3.3. 生成热

优化高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux及该合金所含金属元素单质的晶体结构后,得到了高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的平衡晶格结构以及基态总能量。本文中的生成热是由下式算出:

(2)

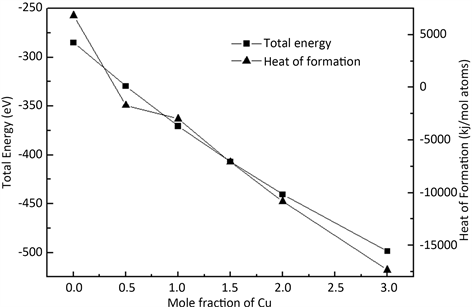

公式(2)中,Eform为生成热,Etotal为基态总能量,xele是金属元素单质的摩尔含量,Eele是平衡晶体结构下的单个晶胞的能量。高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux在Cu元素含量不同时的基态总能量和生成热的计算结果列于表8中,其基态总能量和生成热随着Cu元素含量的变化如图4所示。

金属材料的热力学稳定性是生成的物质能不能转化成其它物质或是其本身有没有自发反应的趋势,这跟吉布斯自由能有关,而生成热和温度共同决定了吉布斯自由能。本文的第一性原理密度泛函理论是一种从头计算的方法,该方法的特点就是没有经验参数,默认温度无变化。既然没有温度影响,本文中影响高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的热力学稳定性的吉布斯自由能就只与生成热有关。表8中计算结果表明高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的基态总能量均为负值。基态是指正常状态下,原子在最低能级,这时电子在离核最近的轨道上运动的这种定态称为基态。基态是电子的稳定状态,因此体系的稳定性就与基态总能量有关。高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的基态总能量均为负值说明高熵合金的体系是比较稳定的,与Cu元素含量没有关系。而高熵合金体系的稳定说明结构内并没有生成复杂相的金属间化合物,是简单的立方结构。高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的生成热在不含有Cu元素时是正,其余为负,说明适当增加Cu元素含量可以提高高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的热力学稳定性。从图4发现随着Cu元素含量的增加,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的基态总能量及生成热都减小,说明高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的稳定性随着Cu元素含量的增加而增强,热力学稳定性也有所提高。

Table 8. The total energies (eV) and the heat of formation (kJ/mol) for the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

表8. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的基态总能量(eV)及生成热(kJ/mol) (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3)

Figure 4. Relationships between the total energy and the heat of formation for the HEA AlFeTiCrZnCux with different Cu content

图4. 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的基态总能量及生成热随Cu含量的变化

4. 结论

1) 高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的晶格常数随着Cu元素含量的增加而减小,密度随之增大。

2) 通过计算不同Cu元素含量的高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux的弹性常数,发现Cu元素含量的增加会降低力学稳定性,但是并不影响其脆/韧性。

3) 本文设置的计算参数下,随着Cu元素含量的增加,高熵合金AlFeTiCrZnCux体系的稳定性及热力学稳定性都有所增强。

基金项目

山西省科技重大专项项目资助(项目号20201102003);运城学院博士科研启动项目(项目号YQ-2017020)。