1. 引言

在中国社会中,同性恋群体大多会受到来自社会的歧视,一项在高校学生中对同性恋的态度调查发现,持有同性恋者需要进行治疗(即认为同性恋是病态)这一观点的人数高达63.4%,“而在这其中对同性恋者持恶心、厌恶态度者各占12.3%和7.2%”(周璐璐,2008),因此在中国情景下的同性恋者受到诸多的限制。对同性恋群体的排斥不仅仅存在于中国,在国外同样也普遍存在,而这无疑对同性恋群体的身体及心理健康都造成极大的影响。同性恋者与异性恋者相比会产生更多的心理问题以及物质滥用问题(Feinstein et al., 2019)。Hunter (1990)的报告指出在他调查的500个青少年同性恋者中,有44%的个体曾经历过反同暴力,同时他们也具有较高的自杀倾向。在社会压力的影响下,同性恋者为了避免受到相应的伤害,往往会选择隐瞒自己的同性恋身份。而与之相反的则是出柜过程,出柜是指男同性恋者、女同性恋者以及双性恋群体将自己的性取向暴露给他人的一个过程,这一过程对于性少数群体的身份形成和融合起着至关重要的作用(Cass, 1979; Rosario et al., 2009)。大量研究发现出柜对于性少数群体的身体健康是有益的(Michaels, Parent, & Torrey, 2016; Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001),但也有研究表明,出柜会对他们产生不良的后果(Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2006)。上述研究可能在一定程度上显示了随着时间西方社会对于性少数群体的社会接受程度的增加。

总的来说,出柜可能会对同性恋者产生深远的影响,Stiles (1987)的自我批露模型显示,处于高度痛苦中的个体更容易暴露自己,而这种痛苦可以通过这一过程得到缓解。而出柜过程同样也可能会带来一些来自个体和社会中的不良影响,例如因此受到家庭与朋友的排斥(Frost et al., 2013)、歧视或偏见(D’Augelli et al., 1998)。在这种情况下,同性恋群体往往会权衡各方面的利益得失,最终采取隐瞒自己性取向的策略来维护自身(Hatzenbuehler et al., 2010)。西方文化背景下,研究同性恋群体的出柜情况以及其与心理健康之间关系的研究有很多,但对处于中国情境下的同性恋群体的相关研究还存在着大量空白。因此,本研究对中国同性恋群体的出柜情况进行了调查,并探究了其与个体的歧视经历、心理健康的关系。

2. 研究方法

2.1. 被试

本研究通过问卷星、豆瓣、百度贴吧等途径发放问卷进行调查,一共收取了913份问卷,筛选无效问卷后,最终样本包括513名同性恋者,其中女同性恋者为192人(37.4%),男同性恋者321人(62.6%),年龄在18至47岁之间(女同性恋:M = 23.97,SD = 4.15);男同性恋者:M = 23.18,SD = 4.96)。参与者需要报告他们的性别、年龄、性取向、性别角色、恋爱情况与教育水平。被试分布详情见表1。

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of homosexual groups

表1. 同性恋群体的人口学特征

2.2. 研究工具

2.2.1. 出柜情况

向被试呈现一个表格调查他们的出柜情况,其中包括向父母出柜、向其他亲属(长辈)出柜、向其他亲属(同辈)出柜、向其他亲属(晚辈)出柜、向朋友出柜、向社会(例如同事、老板等)出柜、未出柜七个选项,请被试选择对不同身份的个体是否出柜。

2.2.2. 性少数群体歧视经历

异性恋骚扰,排斥和歧视量表(HHRDS) (Szymanski, 2006)。这一量表一共14道题目,测量了同性恋者由于同性恋身份而遭受歧视,排斥和骚扰的频率。本研究中将原量表中的“女同性恋”扩充到更广的范围(例如,“您有多少次因为自己是同性恋/双性恋而受到雇主、老板或上司的不公平的对待?”),这一量表采用1 (从不)到6 (几乎所有时间)分评分,最后将得分相加得出总分。该量表显示出很高的信度和效度(Friedman & Leaper, 2010; Szymanski, 2006)。本次研究中克伦巴赫α系数为0.846。

2.2.3. 心理健康

使用霍普金斯症状清单量表进行了心理压力的症状评估(HSCL-21; Green et al., 1988),这一量表是霍普金斯症状清单的缩减版(Derogatis et al., 1974)。这21项自我报告从三个维度来评估被试的心理压力情况:痛苦的感觉,身体上的痛苦和执行困难。被试用李克特计分对症状出现的频繁程度进行评分,从“1 = 一点也不”到“4 = 非常”。本次研究中克伦巴赫α系数为0.919。

2.2.4. 心理弹性

采用6个题目的简易心理弹性量表(BRS)对个体的心理弹性进行评估(Smith et al., 2008)。问卷采用五点评分,被试从1分(非常不同意)到5分(非常同意)对每个项目的同意程度进行评分(例如,“当不好的事情发生时,我很难恢复精神。”)。最后计算量表的平均得分,得分越高表明恢复力越强。简易弹性量表(Brief Resiliency Scale)得分报告的内部一致性在0.70至0.95之间(Smith et al., 2008; Windle et al., 2011)。当前样本的克伦巴赫α系数是0.848。

2.3. 统计分析

剔除无效问卷后,采用SPSS 26.0进行数据录入和统计分析。首先,采用卡方检验和方差分析来分析出柜情况及各量表得分差异。其次,采用双变量相关分析来评估出柜与其他变量的相关关系。最后,本研究采用多元层次回归分析和process插件(Hayes, 2012)来探讨出柜与其他变量之间的关系。

3. 结果

3.1. 男同性恋与女同性恋的出柜情况

3.1.1. 男同性恋与女同性恋出柜情况差异

表2显示了同性恋群体对不同个体的性取向暴露情况。大部分同性恋者自述自己已经向父母、同辈亲属、朋友告知了自己的性取向,而在这当中,向朋友出柜的比例远远高于向其父母、亲属出柜的比例。卡方检验显示,女同与男同在向长辈亲属出柜当中无显著差异,其中c2(1) = 0.394, p = 0.530。而男同与女同在向父母出柜(c2 = 11.742, p = 0.001)、向同辈亲属出柜(c2 = 18.459, p < 0.001)、向晚辈亲属出柜(c2 = 4.559, p = 0.033)、向朋友出柜(c2 = 15.684, p < 0.001)、社会出柜(c2 = 10.397, p = 0.001)和未出柜人数(c2 = 18.306, p < 0.001)上均有显著差异。具体来说,女同性恋比男同性恋更多地向自己的父母、同辈及晚辈亲属,朋友出柜。而男同性恋相对女同性恋来说更不易出柜。

Table 2. Differences in coming out between gay and lesbian groups

表2. 男同性恋与女同性恋群体的出柜差异

3.1.2. 不同性爱角色与恋爱情况同性恋群体的出柜差异

采用卡方检验分析不同性爱角色与恋爱情况的同性恋群体的出柜情况及其差异。卡方检验显示除了女同性恋在向社会出柜中有所差异外(c2 = 9.468, p = 0.024),不同性爱角色的男同性恋与女同性恋在其他出柜情况中均无显著差异。表3显示了处于不同恋爱关系的同性恋群体的出柜情况差异。卡方检验显示女同性恋群体只在向长辈出柜上有所差异(c2 = 7.863, p = 0.049)。而男同性恋群体除了在向朋友出柜上无差异,在向父母出柜(c2 = 13.036, p = 0.005)、向长辈亲属出柜(c2 = 10.441, p = 0.015)、向同辈亲属出柜(c2 = 21.712, p < 0.001)、向晚辈亲属出柜(c2 = 21.338, p < 0.001)、社会出柜(c2 = 12.676, p = 0.005)、未出柜(c2 = 12.116, p = 0.007)上均有显著差异。结果显示处于稳定恋爱关系的男同性恋更多地向自己的父母出柜,向长辈出柜,向同辈出柜,向晚辈出柜,向社会出柜,而处于单身状态的男同性恋更倾向于不出柜。

Table 3. Differences in homosexual outness in different love situations

表3. 不同恋爱情况的同性恋出柜情况差异

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

3.2. 相关分析

各变量间的相关关系见表4。结果表明,同性恋群体的心理健康状况与他们的年龄、恋爱情况、出柜情况、心理弹性、性少数歧视存在显著的相关关系。

Table 4. Correlation analysis matrix for each variable (n = 531)

表4. 各变量间相关分析矩阵(n = 531)

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

3.3. 多元回归分析

本研究采用多元线性回归,探究年龄、性别、出柜情况、性少数歧视和心理弹性这些因素对同性恋群体的心理健康的预测作用。在该回归模型中,各预测变量相互独立(Durbin-Waston检验值为1.868)。回归容忍度为均小于1,不存在多重共线性。该回归模型的F值为49.926,p < 0.001,R2为0.330,调整后R2为0.324。详情见表5。

Table 5. Regression equation coefficient significance test

表5. 回归方程系数显著性检验

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

3.4. 有调节的中介模型

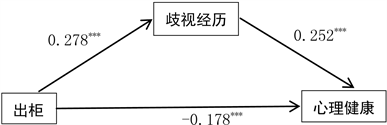

以出柜程度为自变量,同性恋群体的特有歧视经历为中介变量,心理健康为因变量建立的中介模型结果如图1。结果显示,同性恋群体的出柜程度部分通过他们的性少数群体歧视经历影响心理健康,换句话说,同性恋群体出柜程度越高,他们的心理健康水平越低,其中Index = 0.645, SE = 0.157, 95%CI [0.37, 0.99]。

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

Figure 1. The mediation model of coming out and mental health

图1. 出柜与心理健康的中介模型

4. 讨论

本研究旨在研究中国情景下的同性恋群体对不同身份个体的出柜情况以及他们的心理健康水平,探索了性少数歧视经历在其中起到的作用。大部分中国的同性恋者自述已经出柜,与之前的文献一致,同性恋者向朋友出柜的比例远远高于向其父母、亲属出柜的比例(Costa et al., 2013; Ryan et al., 2015)。尽管将自己的性取向暴露给重要的人只是同性恋群体人生发展中的一部分,但对于处于中国传统文化情境下的他们来说,这一过程对他们的生活有着重要的影响。中国是一个以家庭为中心的国家,对于传统社会的绝大多数中国人而言,家族关系是最主要的社会关系(钟新月,2020)。而与之前学者不同的是,男同相比女同更不易选择出柜(Jessica, Victoria, & Baiocco, 2020),这可能与中国传统文化相关,中国传统推崇孝道,生育被作为传统文化中孝道的重要内容延续至今,传统生育观念以“不孝有三,无后为大”为特征,以“传宗接代”为宗旨(李春霞,2008),因此对于男同性恋来说,家庭的接纳更为困难(钟新月,2020)。与处于单身状态的男同性恋相比,拥有稳定恋爱关系的男同性恋者更倾向于选择出柜,这可能与他们拥有更多的社会支持相关。

出柜与同性恋心理健康状况之间的关系目前仍然有着极大的分歧,一些研究者发现出柜与心理健康之间存在着正相关(Lewis et al., 2009),也有学者发现出柜与心理健康水平之间呈负相关(Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2006)。在本研究中,同性恋群体的心理健康状况与他们的年龄、恋爱情况、出柜情况、心理弹性、性少数歧视存在显著的相关关系。年龄、性别、出柜情况、性少数歧视和心理弹性这些因素对同性恋群体的心理健康起着预测的作用。同性恋群体的出柜程度部分通过他们的性少数群体歧视经历影响心理健康,换句话说,同性恋群体出柜程度越高,他们的心理健康水平越低。这一定程度上反映了中国文化背景下的社会对于同性恋群体的接受程度还不是很高,在社会中还存在着对同性恋群体的歧视,进而影响着同性恋群体的心理健康水平。但也有学者提出,同性恋群体出柜的程度取决于很多不同的因素,有可能对于一些人来说会产生有利的影响,而对其他人来说可能又会产生相反的后果,这一后果不仅取决于外在的环境因素,同样也取决于个体本身的特质,因此,同性恋群体的心理健康水平是由个体差异和环境差异等多方因素共同影响的(Frost & Meyer, 2009)。因此,接下来有关同性恋群体出柜情况与心理健康水平的研究应该把个体的性格特征也纳入考虑之中。

5. 结论

女同性恋与男同性恋相比会更倾向于出柜。处于稳定恋爱关系的男同性恋更倾向于出柜,而处于单身状态的男同性恋更倾向于不出柜。年龄、性别、出柜情况、性少数歧视和心理弹性这些因素对同性恋群体的心理健康有预测作用,而同性恋群体的出柜程度部分通过他们的性少数群体歧视经历影响同性恋群体的心理健康。